Previous

ccording to Dr. Eth, a patient’s stay in an inpatient ward should include recreational therapy, occupational therapy, group therapy, individual therapy and family sessions scheduled throughout most of the day. “It’s not like being in a medical hospital where you lay in bed all day,” Eth says. “In a psychiatric hospital you should be involved in therapeutic activities as much of the day and evening as possible.”

Eth also includes “informal conversations with nurses who circulate among the patients,” as a part of the therapeutic milieu.

According to Bluestone, doctor-patient interactions are supposed to be active and frequent. “During the first week [on a psych ward] the patient’s going to be seen [by a psychiatrist for a session] everyday,” he says. “In an emergency room they’re going to be seen ten times a day. We have six beds in that emergency room, every patient is being seen all the time by psychiatrists, talking to them, and seeing a social worker. It drops down as patients stay longer.” Once on the ward, my only interactions with a psychiatrist were two three-minute visits, when he popped into my room to ask if I was having any side effects from the medication and if I was still feeling depressed.

|

Participating in everything that was available on the pysch unit, I attend three groups, each lasting approximately one hour, and a few stretching and dance sessions. One group consists of a game where the activity therapist hands out a stack of cards and we pass them around, read the question aloud--What do you like best about yourself? List two words that describe you--and respond.

Another group, called “community integration,” consists of a group of us sitting around a table with a package of magic markers while the activity therapist slowly and sweetly asks us to draw something in the neighborhood that either keeps us out of or puts us in the hospital: “Michael, do you also use C-Town, is that someplace that keeps you healthy?”

The third group includes a psychologist and another woman who I believe is a psychologist-in-training. One patient who I heard earlier on the pay phone complaining loudly and desperately, “I have absolutely nothing to do here but sleep,” asks “Why am I here? Doctors don’t talk to me, nobody talks to me. Why am I here? Doctors run from me....” It’s a legitimate complaint, but it’s lost because she trails off into delusion. Another patient in the group says, you just have to be humble, do what they say, you can’t fight the system. I contribute maybe three or four sentences.

The Comprehensive Treatment Plan that staff filled out on me states that the social worker will “meet with the patient on an ongoing basis for continual assessment, psychoeducation and discharge planning.” I see a social worker one time in seven and a half days--when she gives me my discharge date and completes my paperwork.

ichael, a Latino in his late thirties, has been angry and complaining loudly to no one in particular all day--sick of being cooped up, bored out of his mind. He paces around, going in and out of his room, doing push-ups, trying to burn off the agitation. No one pays attention. Not one staff member has said a thing to him, not even a “Michael, what’s going on, what’s the matter?” He continues to boil until his mother comes to visit that evening. He starts complaining to her, and his complaints get progressively louder as he hypes himself up. Eventually he stands--he’s screaming now: “GET ME THE FUCK OUT OF HERE, GET ME THE FUCK OUT OF HERE.”

He’s in his mother’s face shouting over and over at the top of his lungs, “I want a discharge date now. I want a discharge date tomorrow.” It goes on and on.

Finally a nurse comes out of the station. “My mother wants to know why I can’t get any damn towels here when I come out of the shower,” Michael demands as his mother meekly shakes her head no.

“Why are you screaming?” the nurse asks him, slightly exaggerating her puzzlement.

“When I went looking for you to ask for a towel, where the fuck were you? Standing in the corner reading a newspaper, that’s where you were. Write that fuckin’ down,” he screams.

He is now in a frenzy, yelling over and over at the top of his lungs, “Get me the fuck out of here.”

Cynthia is the only person who reaches out to him, putting out her hand, saying something like, “Michael, don’t, it’s not worth it.” But he is too far gone.

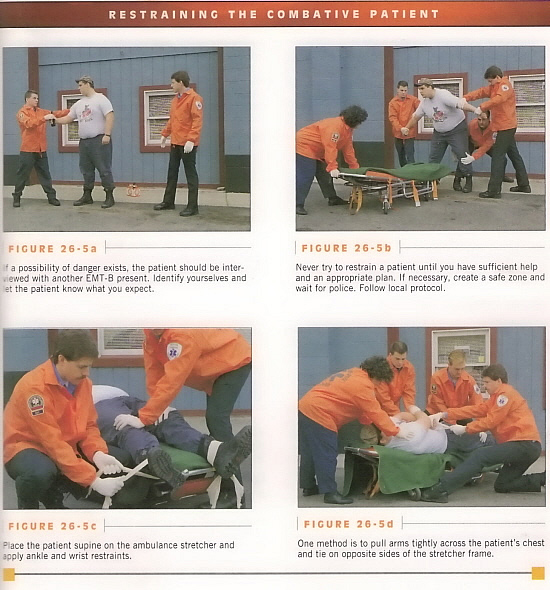

The nurse starts making phone calls for a restraint. Soon, about five young men--therapy aides from other units--appear on the floor. As the aides converge they greet each other, horseplaying, playfully hitting and pushing one another, joshing and joking, loudly laughing and guffawing, giving one another high fives, while Michael loses his mind a few feet away.

One of the aides gets what looks like long lengths of Ace bandages. He asks the nurse, “Do you want him tied down?” The nurse says yes. When Michael sees this particular aide (one of the few workers who occasionally communicates with the patients), he tries to talk to him, saying he doesn’t need to be tied down, he’ll take the medication. But it’s too late. The aide catches my eye as he goes into Michael’s room with the restraint material. “Totally unnecessary, this is totally unnecessary,” he says, apologetically. It seems like he feels a need to explain himself or feels uncomfortable with his actions because I carry myself differently, more like him than a typical patient. Not enough of the other patients have that presence.

As the aides play around outside of his room, Michael assumes the position, spread-eagled on his bed, and is tied down at his ankles and wrists. A nurse comes in after a short while, kneels on his bed and injects him with medication.

Click to Continue