Previous

alfway through my stay I’m called into a room where six professional staff members are gathered around conference tables. I assume I’m supposed to make my case for release. I tell them there is no reason for me to be there, that there is no treatment going on, that I now have a stable place to live, that it seems unfair that I came to the hospital for help and got locked up. They say little in response. In answer to my question of when I would be getting out, a staff member offers a dismissive, “You’ll get out when it’s your time.”

Over the weekend, some of us are paired with nursing students from Medgar Evers College for what my student nurse describes as her homework assignment. She isn’t familiar with the drugs I’m taking and seems to have little  familiarity with psychiatric issues. Well-intentioned, she talks about herself too much instead of listening. She suggests, among other things, that I have a baby to ward off my depression. In our second meeting, she tells me I should stay out of these places, warns me about people being trapped here. She tells me, finally, “You don’t belong here, I talked to that nurse in there,” she gestures toward the nurses’ station, “and she says you don’t belong here.”

familiarity with psychiatric issues. Well-intentioned, she talks about herself too much instead of listening. She suggests, among other things, that I have a baby to ward off my depression. In our second meeting, she tells me I should stay out of these places, warns me about people being trapped here. She tells me, finally, “You don’t belong here, I talked to that nurse in there,” she gestures toward the nurses’ station, “and she says you don’t belong here.”

I respond that I tell them that every day. Why am I still here if everyone acknowledges that I don’t belong here?

“You know, they need to make money,” she says. “They need to do their job; you know what I mean.”

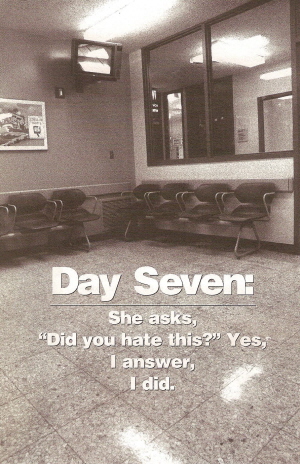

or someone coming to a hospital in crisis, the last thing they want is to lie on a gurney contemplating their situation while the people they’ve turned to for help ignore them, chattering a few feet away. There is no comfort here. The day-to-day boredom is stultifying. For me it was compounded by the anxiety of being locked in a place I didn’t trust, not knowing when I’d be discharged (staff told me everything from 24 hours to 16 days). Initially all I wanted was to get out. Then to be medicated out of my mind. After a few days, I got slightly used to it and alternated between malaise, playing therapist and a Hogan’s Heroes routine--Freddy and I sitting in our room mocking the whole enterprise.

In the Rosenhan experiment all the pseudopatients took notes openly. It was never questioned by staff. In fact, it was described in their records as “an aspect of their pathological behavior.” Little has changed in 25 years. It is almost impossible to be anything but wrong in the hospital. When I acted too normal I earned the scorn of staff for not being sick enough, for trying to freeload sympathy. When I complained about being locked up I was scolded, told that I was there for a reason: I was sick.

For patients who really need help, this is a wasted opportunity. In group therapy, Michael was treated as if he was developmentally disabled. Outside group he was talking about “Fahrenheit 451” and Arafat, and he lent me his copies of Time magazine. Many of the patients were desperate for anything to do, anything to engage them. The one time a newspaper appeared on the ward, people went crazy for it; it got passed around and picked up by a number of patients. Todd started asking to borrow my books; Harold taught me Haitian Creole phrases. I took out a subway map and all the people in my room gathered around, identifying where they live, where we were, how to get from here to there--hungry for a connection to anything outside of the hospital we-are-sick milieu.

Click to Continue