Previous

usan, get away from that door before I tie your ass down,” a staff worker screams at a patient.

Patient: “I want more food.”

Staff: “You’re too fat.”

A staff worker comes in and yells at the top of his lungs, “Leave us the heck alone. All you people do is sit there and watch TV all day while we work, so leave us alone.”

On my first night on the ward, a nurse calls me over to the cage. I bend down almost to one knee to talk into the opening. The nurse speaks to me in the same tone that the admitting nurse had used to ask me about my suspected crack problem. “Why are you here?” she asks. I say I just came into the emergency room one night, said I needed some help. I didn’t expect this to happen to me.

“You wanted some attention, huh?” she says.

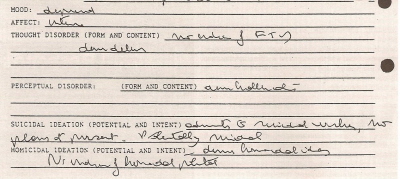

The "Initial Evaluation Sheet" completed in the psych ER classifies the author as potentially suicidal. |

A worker comes in to the room while I’m asleep and says, “Breakfast, don’t you want breakfast?”--without acknowledging that I have no idea when breakfast is served and no alarm to wake me. I get up intending to brush my teeth, make myself presentable, but the worker returns 30 seconds later and in a scolding tone says, “Hurry up, breakfast is going to be gone. You’re going to miss breakfast. Don’t you want to eat?”

A simple request for aspirin is rebuffed with sarcasm. (“I have a headache too.”) A request to identify a pill I’m given is met with annoyed silence. Asking for medication to help me sleep turns into a futile mess of verbal bureaucracy:

Staff: You already got your medication for tonight.

Me: But it didn’t work; it didn’t do anything for me.

Staff: You got your medication for sleep at nine o’clock, it says right here.

Me: I know, but look, I’m still wide awake and it’s 2 a.m.

I came into the ER with a pack of cigarettes that was confiscated, given to the ward staff to dole out to me during four official daily cigarette breaks. I don’t want to smoke, and I try to tell the staff not to call me for cigarette breaks, that I would rather save them for when I’m on the outside.

“No, we have a schedule, rules,” the nurse replies, ignoring what I’m saying. I try again and again each time I’m called to the nurses’ station for my cigarette, Please, please can I just say one thing, please, until the nurse lets me speak and I try to calmly and carefully explain that I don’t want to be called for cigarettes every smoke break. “Can you just take my cigarettes out of that basket so the next nurse at the next cigarette break doesn’t call my name?” I ask.

The next cigarette break, my name is screamed and screamed until I finally go over and again explain. Four times each day this takes place. Finally, one time, tired of explaining, when my name is screamed for cigarettes I go over, take my cigarette and give it to a fellow patient (everybody else was desperate for cigarettes). That gets the staff’s attention. Breaking a rule: that was understood, responded to, attended to. The nurse heads straight for the other patient, makes him return the cigarette, puts other staff on alert. I apologize, say I didn’t know the rules.

ne of my roommates is Todd, the young man I met on my first night in the psych ER. Another is Harold, a vulnerable twenty-something Haitian immigrant who had been working the midnight shift in a fast food restaurant in Brooklyn, even as he was falling apart.

When Harold was in the psych ER, he was floridly psychotic, delusional, constantly chanting to himself, incapable of holding a conversation with anybody. On the ward, after a few days of medication, most of the severe symptoms had vanished. What remains is an anxiety-ridden, frightened, unsure young man, eager to go home, upset that his mental illness has ruined his life, pacing back and forth, worried that he will lose his job at the fast food restaurant. He goes in and out of the room, gets up, sits down, doesn’t know what to do with himself all day.

|

“If I do good, follow all the rules, follow all their treatment, I’ll be able to go home right?” Harold asks me. For him, the hospital is one part flophouse, one part prison, one part continual parole board. He, like many of the patients, is so frightened of somehow acting inappropriately, of being observed acting crazy, of being kept in the hospital longer, that he spends a tremendous amount of energy and is under constant stress desperately trying to act normal. He advises me that if I can’t sleep, I shouldn’t ask for medication--they’ll keep me longer. He himself has difficulty sleeping; awake at 4 or 5 a.m., he resists going out into the day area where he will be seen. He paces madly inside of our room until a respectable 6 or 7 a.m.

“They think I’m sick, they think I’m crazy, that’s why they don’t answer me,” Harold says to me after one interaction with staff. “Better not to ask them anything, right? They’ll think you’re crazy.”

He repeats, like a mantra, “Medicine is good, medicine is good.” But also insists, “We need counseling, counseling brings relief.” I talk to him for both our benefits. “I learned something from you today,” he tells me one day, pleased, “and the time passed.” Over the course of the week, I’m the only one I ever see who listens to his problems, tries to allay his fears, knows anything about him.

He doesn’t know the name of the medication he’s taking, and despite four years of mental illness, two hospitalizations in acute wards and one stay in a state psychiatric hospital, he still has no grasp of the biological explanations for mental illness--or of what’s happening to him.

Other patients have no idea what medications they’re taking, and I don’t see the nurses make any attempt to educate patients about their medications. Some patients have no idea how to petition to get out of the hospital, or how and when to see a psychiatrist or a counselor.

Todd is talking to Cynthia, a kind, religious, middle-aged woman who acts as an informal counselor to many patients on the ward. She was recently told she might be sent to a state hospital. Todd says, “It’s a scary feeling, these people got your future in their hands. You don’t even know what can happen to you. They don’t tell you when you’re gonna get out. You could be here the rest of your life.” Cynthia is mmm-hmmm-ing in agreement. They agree it was a mistake to come here, that they won’t come here again. Todd rarely has any interaction with staff. He just sleeps, eats and comes out of his room occasionally to watch television.

There are countless opportunities for staff members to relate to people on the ward. They simply make little effort to talk or interact with any of the patients. Or even to take the initiative to replace the ward’s one Ping-Pong ball, which cracked my first day there. The therapy aides bring in movies from home to watch on the day room VCR. I rarely see professional staff. Basically, patients can and do spend most of the day pacing the corridors, and nobody does a thing about it.

Click to Continue